This is the 2nd post on the May 31, 2024 special session of the IPAK-EDU Director’s Science Webinar featuring the research of Garrett Wallace Brown and David Bell. Their talk was entitled, “Pandemic Threat is Grossly Misrepresented”.

Part 1 is here.

In Part 1, David Bell expertly deconstructed the shortcomings in the evidence cited to support the zoonotic pandemic threat narrative being pushed by the pandemic preparedness response [PPR] agenda.

That agenda comes with a hefty price tag.

Questions:

How much are the PPR advocates asking for?

What is the data and evidence cited by PPR advocates?

If the touted threat of a zoonotic pandemic are not supported by the evidence, what is the justification for the financial demands that are being put forth?

What are the repercussions on other programs?

Enter: Garrett Wallace Brown

Garrett Wallace Brown is Chair of Global Health Policy at the University of Leeds. He is Co-Lead of the Global Health Research Unit and will be the Director of a new WHO Collaboration Centre for Health Systems and Health Security. His research focuses on global health governance, health financing, health system strengthening, health equity and estimating the costs and funding feasibility of pandemic preparedness and response. He has conducted policy and research collaborations in global health for over 25 years and has worked with NGOs, governments in Africa, the DHSC, the FCDO, the UK Cabinet Office, WHO, G7 and G20. Garrett is Co-Principal Investigator on the REPPARE project.

In May 2024, the REPPARE research group published a report entitled, “The Cost of Pandemic Preparedness”.

In the report, the authors observe:

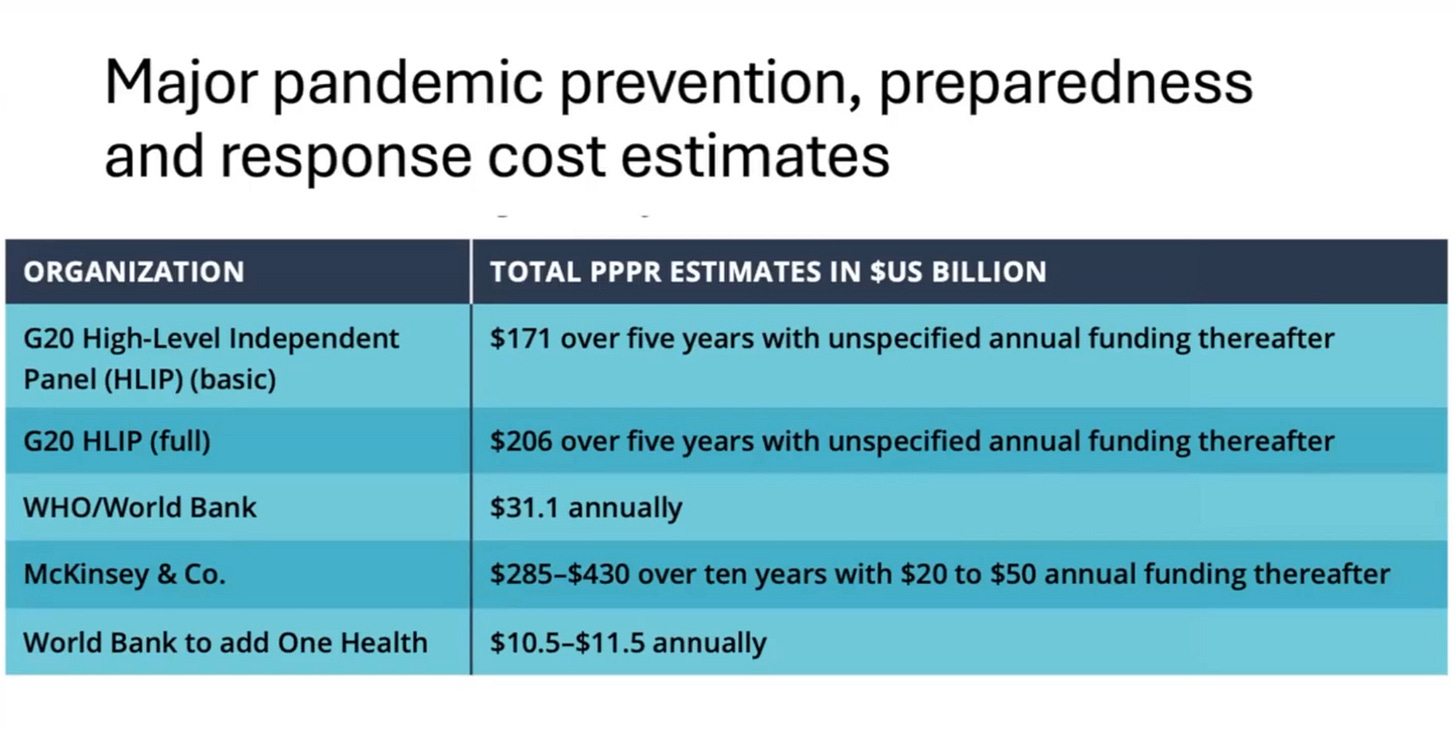

Unprecedented financial requests are being proposed to support this agenda. These estimates range from US$31.1 billion a year, to US$171 billion over five years with unspecified annual commitments, to US$357 billion over ten years, with additional funds of US$10.3 toUS$1.5 billion sought to implement One Health.

The authors continue:

The report finds that there is a general lack of accurate cost estimations for current pandemic preparedness at both the domestic and international level due to poor monitoring, a lack of reporting, and inconsistent definitions about what constitutes pandemic preparedness. That current cost estimates are based on a small evidence-base that is self-referential and under-scrutinized creating a circular evidence and citation base resulting in a false perception of rigor and counter-verification.

and

The estimates of required investment fail to consider significant associated opportunity costs, thus threatening to shift scarce resources from high impact investments on greater disease burdens with considerable resultant negative health outcomes.

The estimates are significant and would constitute anywhere from 25% to 55% of current global ODA [Official Development Assistance] spend for health, representing a disproportionate investment for an unknown future disease burden. This defies traditional practices in public health, which would weighany benefit of pandemic prevention against other disease burdens and health financing needs.

An important detailed criticism raised by the report considers the PPR claim of rising economic impact attributed to selected disease outbreak over the last 3 decades.

The authors are critical of this representation in many respects:

The rising costs per pandemic illustrated in Figure 6 are likely to reflect more the choice of response than an increasing disease burden. As a global public health body, WHO has a responsibility, and mandate, to assess this carefully and advise PPPR policy on the basis of evidence. Was the cost of the 2003 SARS outbreak, which killed approximately 800 people, the equivalent to 6 hours of tuberculosis deaths, a proportionate response? Or, as discussed above, the COVID-19 response? Making such a determination requires the careful weighting of evidence.

The authors also find the documented financial burden of HIV, tuberculosis and malaria to be misrepresented by PPR advocates:

The estimated total annual economic impact of HIV, tuberculosis and malaria of approximately US$22 billion per year in Figure 6 is inconsistent with (far lower than) many other sources. For example, a study published in The Lancet estimated that the 1.4 million deaths from tuberculosis in 2018 resulted in US$580 billion in full income losses. A KPMG report further estimates that during the period of 2000-2014, tuberculosis-related mortality caused US$616 billion in lost economic output. A Lancet study on HIV argued that between 2000 and 2015, US$562.6 billion was spent on HIV/AIDS worldwide, which would equate to US$37.5 billion per year for HIV alone.

Further, disease mortality for tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV dwarfs COVID-19 mortality. It’s an apple to oranges comparison—COVID-19 isn’t even close.

Including COVID-19, the mortality total from all five diseases listed in Figure 6 rises to just over 7.2 million. Although this is not insignificant, it is a much smaller mortality burden than that of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria over the same period (at approximately 120 million deaths). In addition, wider tools for estimating disease burden such as disability-adjusted life years lost (DALYs) would provide a very different picture, since COVID-19 mortality was largely restricted to those aged over 75 years, whereas malaria largely kills children under the age of five. As the graphic on sub-Saharan Africa in Figure 7 illustrates, when calculated in terms of DALYS, reported COVID-19 cases represented a very low burden compared to HIV, tuberculosis and malaria in this population. However, the recent Global Burden of Disease study estimates COVID-19 to be responsible for around 75% of total pandemic-era excess mortality and to be the leading cause of DALYs lost in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa. This illustrates a large degree of uncertainty with respect to the real burden of COVID-19 as compared to the effects of mitigation measures and other disease burden.

Further, the proposed shift in priorities toward ‘pandemic preparedness’ is also observed in cuts to positive programs supporting things like basic health care and nutrition.

In the short video excerpt below, Garrett Wallace Brown, lead author of the REPPARE report, breaks it down. Watch.

Plain Language

Academics and policy analysts don’t always say things in plain language.

This is to be expected; and doubly so in this particular space. It comes with the territory—there are boundaries. Claims and criticism must be justified and supported by evidence. Intellectual and scientific rigor are fundamental, even if the authors of the official reports out of global health institutions appear not to value such things at all. And as should be obvious, politics and moneyed agendas are ever-present.

But academic study and critique doesn’t always translate well outside academia.

Sometimes a story can be more illustrative.

An allegory

Imagine your family is visited by a group of well-dressed professionals.

As you open the door, you’re surprised by their slippery agility. They flash you credentials that seem official, but you really have no way of judging.

You have never met these people before and have not invited them in. But everything is a blur, they talk quickly and with complexity. It’s all moving too quickly to process. Before you realize it, they are in your home, sitting with you at the table.

They are very grave and explain that your accustomed way of life is over. You must rearrange your financial priorities. You are directed to set aside as much as half of your budget for them.

Confused, you haven’t yet paused to consider who these professionals are and what authority they actually wield. Still, without even doing the math, you know it will impact everything. You know that many of the costs you think of as essential will feel the impact; in fact, the impact may be so profound, it may force you to move to reduce rent, consume less food or purchase lower quality food, forego healthcare, and more.

Worried, you ask what this enormous portion of your finances will be going toward.

The professionals smile and open their briefcases, pulling out a stack of reports, laying them out on the table in front of you. Tables, charts, graphs. So many numbers. It all looks very convincing, even though you aren’t really sure what you’re being convinced of.

Data and graphics, brandished like a loaded gun. It feels compelling, urgent.

After staring at the array of smartly dressed documents spread across the table, but somewhat unequipped to digest, you sheepishly ask: “But what does it all mean?”

“It means, if you don’t listen to us, you will die.”

The tenor of the scene above should feel familiar. It is a well-worn theme in espionage thrillers and mafia films.

In these films, the antagonists are typically physically menacing and threatening. Acts of violence are used to induce fear in their victims, and thereby gain compliance. In the above scene from The Equalizer, the dirty cops return to the scene of the small restaurant that recently burned because the owner refused to pay the protection money. Traumatized by the act of arson, the cost to her livelihood, and the actualization and anticipation of violence, the woman relents and pays the ransom.

A great many victims caught in a protection racket hardly question the necessity of compliance. It can become an unquestioned part of reality. They accept the terms of their exploitation because they have been traumatized and don’t think of resisting.

Like these victims, the world has also been traumatized.

Virtually no one wants to see a repeat of what has just been lived through.

And yet, the fact of the matter is, that the world has been subjected to staggering acts of violence in the COVID era, but that violence has been mostly blamed on a virus.

The difference with what is happening in public health policy vis-a-vis PPR is that instead of gangsters, mafiosi, or dirty cops, we are facing off with the unelected and faceless weaponization of ‘civil society’ and ‘public health’ on the global public.

The lies are visible everywhere. Well-dressed and packaged, but to be clear: the intention is to mislead and obfuscate.

Nevertheless, what is being promulgated amounts to extortion.

Wikipedia defines extortion like this:

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit (e.g., money or goods) through coercion.

As with many words, etymology brings a more nuanced and complete understanding:

The bits worth highlighting here are:

“duress, menace, authority, or any undue exercise of power”.

Extortion need not be meted out at the end of a sword or gun, or physical force of any kind. Fear can be the most powerful of motivators. And for the victims of trauma, the scars of that memory can serve to amplify the power of fear, even at the level of nations.

In the case of pandemic preparedness policy, this is duress imposed by the fraudulent abuse of influence. It is the policy of cultivating a narrative of exaggerated threat without evidence of demonstrative value.

Academics can’t characterize it like this. There are boundaries that must be respected.

Consider the following rhetorical question, framed by the allegory we began with:

How different is this from a gangster coming into your place of business and demanding half of the take—for ‘protection’?

Most are familiar with the adage, “Give someone an inch and they’ll take a mile.”

In that context, it’s worth reflecting on the juxtaposition highlighted by Garrett Wallace Brown: the entire WHO annual budget is around $3.8 billion, compared to the bloated PPR proposals of a quarter of a trillion dollars for pandemic preparedness.

Let that simmer.

More from this talk coming. Stay tuned.

#questioneverything

Subscribers to the IPAK-EDU Director’s Science Webinar get full access to webinar recordings, including this session with Garrett Wallace Brown and David Bell.

Your support of the webinar and IPAK-EDU makes this possible!

Go here to read the report for yourself:

Information wants to be free—and over 90% of the content here is accessible to anyone. But everything takes care and time. If you like what you see, and you’re willing and able, consider leaving a tip. Every little bit helps. Thank you!